Pain-Free Versus Pain-Threshold Rehabilitation Following Acute Hamstring Strain Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial

HickeyJT, Timmons RG, Maniar N, Rio E, Hickey PF, Pitcher CA, Williams MD, and Opar DA. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy , 2020

Review Date:

04February 2021

Review Group:

- Mr Patrick Carton, Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon, The Hip and Groin Clinic.

- Mr David Filan, Senior Research Assistant, UPMC Whitfield.

- Dr Karen Mullins, Research Assistant, UPMC Whitfield.

- Mr Derek O’Neill, Senior Physiotherapist, UPMC Whitfield.

- Dr Dualtach Mac Colgain, Sports Medicine Doctor, UPMC Whitfield.

- Mr Michael Bowler, Physiotherapist, UPMC Whitfield.

- Ms Sarah Coughlan, Physiotherapist, UPMC Whitfield.

Title

The title focuses on an important research question which has substantial clinical relevance.

Aims

The main aims are clearly set out in the introduction and based on a prior published systematic review by the research team: 1) to identify whether a pain-threshold approach to rehabilitation of a hamstring strain injury (HSI) differs from a pain-free approach with respect to return to play clearance (RTP) timeand 2) to determine whether adopting a pain-threshold approach to rehab can improve measures of knew flexor strength, bicep femoris long head (BFLH) fascicle length, fear of movement and re-injury rates.

Methods

The authors present a comprehensive methodology. The Cochrane risk of bias tool was used to guide practice and as sucha clear and detailed randomisation process was described in the paper. The blinding of assessors was also highlighted throughout, although it is not fully clear whether the lead physiotherapist/lead author who supervised patients and determined RTPclearance was blinded to group allocation.

A priori power analysis was conducted to determine sample size. The size of the effect included in the analysis was large (1.2) which was based on two prior randomised control trials comparing rehabilitation which emphasised lengthening compared to conventional exercises. The authors state they required 29 participants, but it is not clear whether this was 29 participants in total or whether this allowed for two groups within the entire sample for comparison. There are questions therefore regarding the overall power of the study.

Participants were invited to join the study if they had a suspected HSI which was later confirmed in clinic by clinicians who were blinded to the group allocation. MRI was not used to diagnose the HSI, the lack of which is rightly highlighted by the authors as a limitation of the methodology. The absence of MRI does not allow for differentiation between the nature andseverity of injury which will undoubtedly have an influence on the rehabilitation process and return to play.

The strength testing was carried out using a previously described apparatus which was found to have moderate to high reliability for the strength tests reported on in this paper (knee flexor strength at 0o/0o of hip and knee flexion and 90o/90o hip and knee flexion).

BFLH fascicle length was determined using ultrasound by a clinician blinded to group allocation. Fear of movement was determined by the lead author using the 17 item Tampa scale of Kinesiophobia.

The rehabilitation protocol is well described and supported by appropriate literature throughout.Assessments were carried out at diagnosis, RTP clearance, and 2-months following RTP clearance while the number of re-injuries in the 6 months following RTP clearance was determined by phone call.

Results

43 participants were included with 22 in the pain-free group ad 21 in the pain-threshold group. All participants were male. There was no statistical difference in the median time to RTP clearance between groups (15 days in the pain-free group and 17 days in the pain-threshold group).Similar improvements in both groups for knee flexor strength at 0o/0owere recorded, while greater knee flexor strength improvements at 90o/90o which were sustained at 2 months were noted in the pain-threshold group. Both groups recorded increased BFLH fascicle length at RTP clearance compared to diagnosis. This improvement was greater in the pain-threshold group at the two-month post- RTP clearance follow up. Similar reductions in fear of movement were recorded for both groups. Four participants suffered a re-injury in the following 6 months:2 from each group.

It would have been useful to the reader for the authors to include results from any statistical analysis between baseline characteristics of the groups in table 4. Again, the lack of MRI findings is a limitation here as there is no opportunity to classify injury types and severity within the rehabilitation approaches for comparison. Considering one participant achieved RTP clearance after 6 days there are questions as to the severity of the injuries to begin with. It cannot be concluded therefore that a pain-threshold approach would apply to all HSI.

Table 3 which details the return to play clearance criteria needed to be expanded upon. It was not stated whether the lack of pain or apprehension during sprinting was only for linear running. Whether this translates to multidirectional field sports is unclear. Kicking was also not assessed.

Participants were instructed to only complete this rehabilitation protocol, yet they were encouraged to return to training gradually with their respective sports teams. This could have led to some element of performance bias whereby participants were also exposed to some additional rehabilitation. Following RTP clearance participants were encouraged to continue with aspects of the rehabilitation program but this was not enforced or monitored. The decision to return to play was also not determined by the investigators here, rather the team managerand participants themselves. It is therefore not possible to correlate the rehabilitation protocol with return to play.

It was not stated why the participants were followed up for six months only and not a full season following the injury. While no statistical analysis was possible for the re-injury rates, it appears as though those in the pain-threshold group had a shorter re-injury time. With a longer follow up and greater numbers, analysing this aspect would be extremely useful to health care professionals.

Review Group Summary

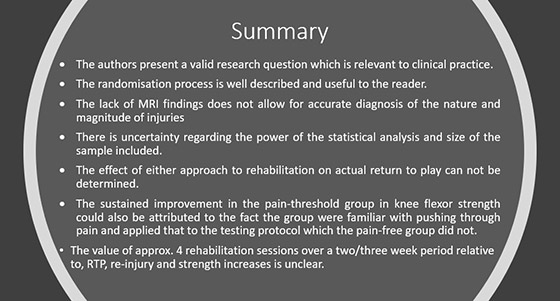

- The authors present a valid research question which is relevant to clinical practice.

- The randomisation process is well described and useful to the reader.

- The lack of MRI findings does not allow for accurate diagnosis of the nature and magnitude of injuries.

- There is uncertainty regarding the power of the statistical analysis and size of the sample included.

- The effect of either approach to rehabilitation on actual return to play can not be determined.

- The sustained improvement in the pain-threshold group in knee flexor strength could also be attributed to the fact the group were familiar with pushing through pain and applied that to the testing protocol which the pain-free group did not.

- The value of approx. 4 rehabilitation sessions over a two/three week period relative to, RTP, re-injury and strength increases is unclear.

The results indicate that delaying progression through a rehabilitation program until pain free movement in each phase is achieved may not be necessary. The limitations in methodology including the short intervention time and small sample size compromises the validity of the conclusions made regarding strength improvements over time.