The Facts and The Truth

Mr. Patrick Carton MD FRCS (Tr&Orth)

Specialist Hip and Groin Surgeon,

Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon,

Whitfield Clinic, Waterford

Introduction:

One of the biggest risks facing many GAA football and hurling players is progressive damage of their hip joints forcing an early end to their sports careers and developing arthritis of the hip, eventually requiring joint replacement.

As a surgeon who specialises in hip surgery in athletes, I am faced with comforting such devastated GAA players every single week in my practice. The story is almost the same every time – the players have been aware of progressive stiffness and inflexibility around their hips and hamstrings for a number of years. The stiffness is present for a few days following training and playing and in many cases is associated with progressive groin pain and lower back discomfort. In the morning following a training session, many players even find it difficult to put on their socks and shoes.

These players attend the team physiotherapist regularly for rubdowns, deep massage, stretching, gluteal and core strengthening. In many cases they have attended a number of therapists and some are advised to have unnecessary steroid injections into their hips or groins. Eventually a number of years later they attend my clinic in the hope of receiving ‘hip repair’ surgery and to return to their sports symptom free – but they are too late!

Clinical examination reveals significant loss of hip movements on one or both sides, X-rays and scans demonstrate irreversible damage to the cartilage surface of the hip joint from chronic ‘hip impingement’. At this stage the condition has advanced too far for repair surgery and unfortunately, the best advice I can give these players, is to give up playing their sports.

For many of these young players in their late twenties and early thirties, they are facing the prospect of hip replacement in the near future and this news is difficult to comprehend but it is a reality I see all too commonly at my sports clinic, in Waterford.

What Is Hip Impingement?

Over the past ten years there has been an increasing awareness of the long-term effects of years of intense training and competition, on the hips. Rapid deceleration with acute twisting and turning places significant stresses on the hip joint; this coupled with a developing skeleton during adolescence results in structural changes to the natural shape of the ‘ball and socket’ (hip joint) creating a mechanical block to the normal movement of the hip – this is known as ‘hip impingement’.

The bony deformity develops further as participation in sports continues, the repetitive abnormal movement of the hip joint resulting in progressive damage to the cartilage surface of the joint and the fibrocartilage seal around the edge of the socket, known as the labrum. The damage eventually becomes irreversible and widespread – the first stage of arthritis is now present.

How does the damage to my hip begin?

The head of the femur (‘ball’) is round and should fit perfectly within the pelvic ‘socket’. The socket should be shaped to cover enough of the ball to keep the joint stable but not to limit its range of movement. Strain placed on the socket during sports results in the edge of the socket (‘rim’) becoming more pronounced; this bony prominence is known as a ‘Pincer’ deformity and progressively increases in size resulting in restriction of hip movement and stiffness of the joint.

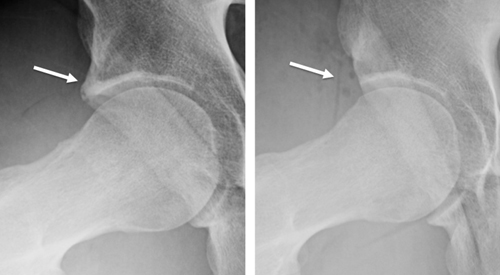

Figure 1. (left) arrow pointing to pincer deformity; (right) post-operative x-ray image showing resection of pincer deformity

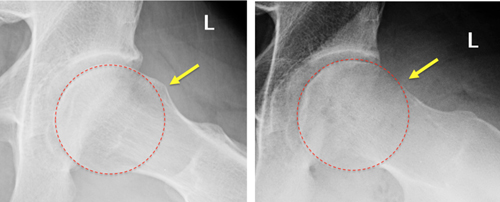

With continued participation in sports, despite having early restriction of motion, repetitive abnormal contact between the head of the femur (ball) and the prominent rim of the socket (pincer) results in the head of the femur becoming thicker and misshapen (flattening) known as a CAM deformity (figure 2.). CAM deformities can be seen in young sportsmen as young as ten years old.

CAM Deformity: see Figure 2 below or click to watch video

Figure 2: (left) arrow pointing to CAM deformity; (right) post-operative x-ray image showing resection of CAM deformity

What are the first symptoms of a hip problem?

The ‘ball and socket’ is no longer a perfect fit and begins to function abnormally with the head of the femur making regular abnormal contact with the prominent rim of the socket. This places a restriction on the natural movement of the joint increasing the strain on the muscles and tendons around the hip. It is at this stage when the young GAA player (commonly 17-20 years of age) will begin to feel stiffness after training and playing, often lasting a couple of hours after sports and then beginning to settle again. Most players put this down to a hard training session and many unfortunately consider this normal!

These young players often complain of tight hamstrings and recurrent hamstring strains are a common symptom associated with hip dysfunction from underlying impingement.

Most players are able to tolerate this level of mild to moderate symptoms and keep training and playing. It is often at this stage when players become a regular attender to the physiotherapist for stretching and massage to help deal with the stiffness. This often helps in the short term at the early stages of hip impingement but becomes less useful as the condition progresses.

The first onset of pain!

The progressive impingement places significant strain on the cartilage surface of the hip, which eventually begins to tear. At this stage the GAA player will begin to experience groin pain. Most players (and many doctors/physiotherapists) are unaware that the groin pain is coming from the hip joint and many players are told they have conditions such as osteitis pubis, Gilmore’s groin, adductor strain, hip flexor strain, and many more!

In some cases, the pain may become so intense that players are given unnecessary steroid injections in an attempt to mask the pain.

We believe giving steroid injections into the hip in young athletes with hip impingement is inappropriate and completely counter-productive – temporarily masking symptoms will permit players to feel less pain during sports and will result in continued and potentially accelerated damage to the cartilage of the joint.

For the majority the groin pain is present but tolerated and training and playing continues often for another season or two before the combination of the persistent hip and groin stiffness, discomfort and intermittent sharp pain force the player to stop training and playing altogether – many players at this stage never get back playing again!

Can Hip Impingement Be Treated Without Surgery?

There is a very poor ‘body of evidence’ that supports the conservative (non-surgical) management of hip impingement.

In a worldwide search for all published literature relating to the non-operative treatment of hip impingement(1) there were only five poor quality papers that described the treatment effect of non-operative care. No randomized trials were identified. Analysis of the quality of evidence reviewed was very low for 3 of the studies and low for 2 studies according to the GRADE recommendations.(2)

Two studies (with low quality evidence) did attempt to assess improvement in patient outcomes:

A study by Emara et al (2011)(3) assessed the outcome of 37 patients with mild hip impingement treated with physiotherapy and activity modification and concluded that ‘providing patients can modify their activities of daily living to adapt to their hip pathology then good early results can be achieved without the need for surgery’.

All patients had ‘a normal shaped femoral head’ and an alpha angle less than 60 degrees (over 55 degrees is considered abnormal) – with this inclusion criteria it is very likely that the majority of patients included in the study did not even have hip impingement to begin with!

Patients were not permitted to cycle, or squat; patients were requested to prevent internal rotation and flexion of the hip (essentially ruling out twisting and turning sports such as GAA football and hurling) and running on a treadmill was not allowed.

Of note despite complying with this very restricted protocol, 10 patients (27%) at 2 years still had significant pain and symptoms, 4 of which underwent hip surgery. In the rest of the group significant improvements in their outcomes were observed but physiotherapy made no improvement in range of hip movements.

This study is of very poor quality and does not represent hip impingement in sports like GAA football and hurling. The extremely restricted therapy protocol is completely unrealistic for any GAA player who wants to continue in their sports.

In a second (low level evidence) study, Hunt et al (4)examined the non-operative treatment for 52 patients with non-specific hip pathology. 85% of the patients were female and only 18% of cases were due to hip impingement. 56% of patients failed non-operative management and required surgery; this group had a significantly higher activity levels. The other 44% continued with non-operative therapy. Attendance for physical therapy was very varied with an average of 6 sessions (range 1 – 19) and at a variety of centres with different therapists.

At one year follow up outcome analysis suggested similar improvements in the 2 groups but the authors acknowledged the small study numbers, the high level of females patients, low number of hip impingement cases and the poor compliance and variability with physical therapy protocols make interpretation of these results unclear.

There are many review articles discussing the non-operative treatment of hip impingement, in general; in these articles when details were provided for physical therapy among the review and/or discussion articles, none provided references to evidence that support the therapy regimens proposed. The proposed treatments were simply unsupported opinions with no evidence base.

Non-Operative Treatment – Conclusion:

There is general agreement amongst hip surgeons that a trial of non-operative treatment should be undertaken, by any athlete with hip related pain, for a period of at least 3 months before surgical intervention should be considered.

Initially, a period of rest and activity modification, with medication (anti-inflammatory) should be advised. Avoidance of simple day-to-day aggravating factors such as squatting, stooping, crossing the legs, getting in and out of a car, rapid twisting and turning, sitting slouched forward, etc., may be helpful. As the initial pain begins to settle, more specific physical therapy guidelines can be introduced.

There is no evidence to support specific physical therapy treatments but it is considered important to avoid extremes of hip range of motion and attempting to improve passive movements of the hip by stretching may be counter-productive. Emphasis should be placed rather, on addressing muscle tightness (iliopsoas, hamstrings, rectus femoris) and weakness (core stability and posture, and optimise the alignment and functional mobility of the joint.

Sports clinics may promote rehabilitation programmes for GAA players with hip impingement ‘without the evidence’ to support their methods.

In more active athletes such is in GAA players there is no evidence to support benefits of non-operative treatment (e.g. physiotherapy) for symptomatic hip impingement (> 3 months).

The real danger posed by continuing to play with symptomatic hip impingement is the progressive and irreversible damage to the hip cartilage.

The Growth of Surgery for Hip Impingement:

Surgical rates for the treatment of hip impingement and labral tears has escalated over the past 15 years; an 18 fold increase has been observed worldwide between 1999 and 2009; in Ireland there has been a significant increase in cases surgically treated over the past 5 years.

There are many valid reasons for these increases including better awareness of hip impingement, higher referral rates from physiotherapists and sports doctors, more availability of surgical centres, improved surgical techniques, wider surgical indications and improved postoperative success and return to sport.

Throughout the economic recession in Ireland there was a significant drop out of private health insurance policies, with more GAA players therefore claiming through their club insurance policies instead – this also created an ‘increase’ in surgery cases therefore going through the GAA insurance scheme.

The numbers of GAA players treated annually in Ireland are still relatively small when compared to the total number of athletes regularly participating in GAA sports.

With any new and developing technique demand for treatment naturally will initially increase, often due to a ‘backload of players’ with chronic symptoms but there are signs that we have already reached the tipping point and over the next few years numbers are likely to drop significantly as the backload reduces, private health insurance increases and the indications for surgery become more clearly defined.

The decision to perform surgery is never taken lightly and is done so following failure of conservative treatment and strong clinical evidence of hip pathology on clinical examination. X-rays and MRA scans are utilised to identify bony abnormalities and cartilage or labral damage in the hip joint.

In our clinic, athletes (who have undergone ‘sports hip repair’ surgery) are advised to undergo a period of conservative/physical therapy for at least 3 months, before surgery is considered for continued symptoms. On average, non-operative treatment has been undertaken with 3 separate practitioners (physiotherapy/sports doctors) before attending our hip and groin clinic, in Waterford and symptoms of hip impingement have been present for an average of 2 years.

Will Hip Impingement Go Away?

Hip impingement is a progressive condition. The bone deformities are permanent and will become more evident with continued participation in sports. The abnormal contact between the ball and socket will continue and damage to the cartilage of the joint will increase.

This will not go away unless the player essentially stops playing GAA sports.

There is no evidence that Physiotherapy or steroid injections are in any way useful as a treatment and they will certainly not make hip impingement go away.

Do All Labral Tears and Hip Deformities Need Treated?

The answer to this commonly asked question is NO. There is much confusion over the true incidence and relevance of labral tears and hip deformities. Both are extremely common in athletes and do not need treated unless they become symptomatic. Once symptomatic, then damage is occurring to the hip joint and should be treated.

Is Surgery Successful for Hip Impingement?

There is an overwhelming body of evidence that demonstrates the successful results of keyhole surgery in the treatment of athletes with symptoms from hip impingement. Hundreds of good quality peer-reviewed research papers in the most respected sports and orthopaedic journals from around the world support the success of surgery.

In our clinic in Waterford, we have a 93% success rate in treating athletes and have performed over 1500 ‘sports hip repair’ surgeries in athletes from many sports (including GAA football, hurling, rugby, soccer, tennis, boxing, running, etc.) at every level (professional, international, national, inter-county and competitive).

In every case, there has been a failure of non-surgical treatment before making the decision to operate.

The benefits of surgery include:

- Resolving the chronic pain and stiffness in and around the hip and groin

- Players returning to GAA football and hurling symptom free

- Removing the abnormal bony deformities which will cause irreversible damage to the hip joint leading to arthritis

Can Surgery Cause Arthritis?

Poorly performed surgery can cause damage to any joint and it is important that GAA players choose their surgeon carefully. Carefully performed surgery by an experienced hip impingement surgeon will NOT cause arthritis. Continuing to play with symptoms from hip impingement WILL result in progressive damage that will lead to arthritis. Removing the abnormal bone deformities and repairing the labrum and capsule of the hip will remove the majority of the reasons why arthritis could develop in the hip and should therefore help to prevent arthritis.

The most important factor in long-term success following surgery is early referral before irreversible damage has occurred.

Results at our clinic show that players referred early for surgery have a more successful outcome than those who have symptoms for over two years.

In Summary:

The hip joint plays a central and pivotal role in every movement GAA players make on the pitch. It is no surprise that over time, following thousands of hours of intense training and competition, structural changes to the joint and progressive damage to its cartilage surface can result.

There are a number of factors, which may increase the rate of damage to the hip joints:

- Abnormal morphology (shape) of the bone structure to either the femoral head (ball) or the pelvis (socket)

- In some players there may be abnormal shape to the hip from birth

- In the overwhelming majority however the abnormal shape develops through adolescence (12 – 17 years)

- Increased intensity of sports

- Players who train intensively and regularly are more at risk

- Playing in more than one code and at a number of levels (club/college/county) or also playing soccer/rugby

- High demand training – squatting with weights, cutting maneouvres, hurdles, pike jumps, etc.

- Stretching and excessive ROM of the hip joints to improve stiffness is counter-productive and can increase the impingement

- Playing with symptoms

- Stiffness after activity

- Recurrent hamstring tightness

- Hip inflexibility

- Recurrent groin pain

- Reduced range of hip movements

Mr. Carton is a specialist in hip and groin sports surgery. He has more experience in ‘sports hip repair’ surgery than any other surgeon in Ireland. The results from his surgery are presented regularly both nationally and internationally.

Mr. Carton is internationally renowned for his surgical skills teaching his ‘hip repair’ techniques to surgeons from all over the world and he is a faculty member of the International Society for Hip Arthroscopy.